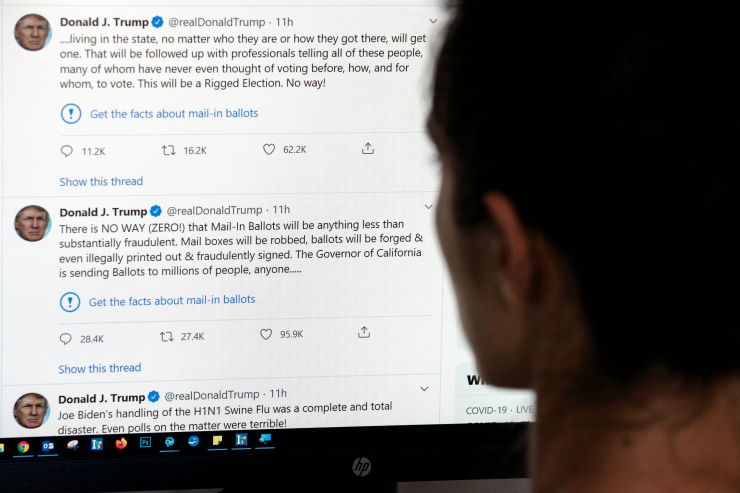

As people all over the country protest the police killing of George Floyd, social media has become the medium for amplifying marginalized voices, organizing and reporting events. It’s also where President Donald Trump and other politicians are responding. But in just the past few days, Twitter has flagged the president’s tweets, and Snapchat essentially deplatformed him.

Bots and bad actors are swarming social media with misinformation, yet these platforms often spark awareness of injustice in the first place. I spoke with Nicol Turner Lee, a fellow at the Brookings Institution. She says these tools are as powerful for black voices as they are dangerous. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

Nicol Turner Lee: I’m a huge fan of being able to use our technology to share our stories. That is how Black Lives Matter was created. But what we have to also realize [is] we need leadership to use that technology to also speak to the people. My heart sinks at what we’re seeing dictated and portrayed through technological interfaces as a new public square is giving us two visions of two Americas. There’s one side that really cannot breathe right now, during a pandemic, and we have no way out.

Molly Wood: I was having this debate with a friend this morning, where she was like, “Honestly, would everything be better if we just shut down Twitter? Seeing people attacked by the police is a form of abuse.” But on the other hand, were it not for these mediums, the video of George Floyd’s death would not have become public.

Turner Lee: You have platforms which are very dominant in terms of their medium. Print newspapers and local radio and television stations are becoming more and more extinct, so there are not many places that people can turn to. The second thing is, like you said, you have a tool that has been used for organizing. My daughter showed me a tweet which basically said, “Hey, come down with your mask and your water and your phone charged,” and that’s very different from the telephone tree of the ’60s.

Wood: When you look at the difference in reaction between Twitter and Facebook — civil rights leaders met with Facebook this week and came away saying this huge platform is not going to help — does it really help that much if Twitter says, “We’re going to hide this tweet behind this filter, but it still exists”?

Turner Lee: It is always very challenging, particularly since we know that conservatives feel bias when they interact with social media platforms, the same way that Black Lives Matter feels bias. The key thing is, there’s a responsible use of a platform, particularly in the midst of the civil unrest. Police brutality has been publicized and shown on Facebook for years — I applaud them for that — but at the same time, when the highest leader in the government is in a position to create the type of turmoil that will result in worse economic and racial stratification and inequalities, hold him accountable the same way that you would hold an individual for a militia group or an African American who may be spouting rhetoric on their side. Don’t exempt him.

Related interview: More insight from Molly Wood

The Arab Spring and other protest movements have been organized on social media, and the technology keeps evolving. The tool of today’s protests is the live stream. Violence by police, broken store windows, peaceful marching. We can still argue about what’s happening, but in many cases it’s happening live for the world to see. Becca Lewis researches the politics of technology and media at Stanford. I talked to her about the stories of these protests and how they are being told.

Becca Lewis: Cable news has to fill a certain amount of time, so you have a lot of talking heads [and] it leads to favoring in-studio PR statements. It leads to easy facilitation of communication between the police and the media. Whereas, when you have on-the-ground coverage from individual citizens or independent news outlets, a lot of times you don’t have those constraints. One of the most striking cases I’ve seen of this on-the-ground coverage is the independent media organization Unicorn Riot, who has had an on-the-ground reporter throughout all of the Minneapolis protests, and also was spending a significant amount of time talking to the community members, which is something that you’re really not getting in the land of cable news or even print news.

Wood: When there is so much information, even more than there ever was, moving exponentially faster in real time, and we know there are huge, coordinated disinformation campaigns, how are those campaigns taking advantage of this moment?

Lewis: Disinformation campaigns thrive on confusion, and a lot of times the goal is not necessarily to get people specifically believing in one narrative or another, it’s to seed doubt in people’s minds. And because these protests are fairly structureless, they’re not coming from a specific voice of leadership, there’s a lot of room for interpretation. There’s a lot of confusion, even on the ground. That, in some ways, becomes a perfect opportunity for disinformation merchants to inject their own narratives into the conversation and use it as an opportunity to sow discord.

Wood: But it sounds like you’re saying to really have a 360-degree picture, do we need to be looking at all of it? Are we at a point where there just really is not one trusted source?

Lewis: The reason that I point to groups like Unicorn Riot is because I actually think one of the biggest missing links here is the role that traditionally has been provided by local news. The people around this reporter recognized him, had seen him before, trusted him and therefore were willing to share their stories with him. I don’t know how we’re going to see more of that, what that means, but I do think that local trust is a place to start.

Also watching:

There is much more reading about how there are cameras everywhere in America, for good or for ill, from the Washington Post. Taylor Lorenz wrote about supercuts of police violence that are racking up tens of millions of views online in The New York Times. And read more from the Verge about Snap’s decision to stop promoting President Trump’s account on its Discover page. It’ll still be there and show up in search results, but it won’t be amplified. Previously, Trump had shown up consistently in the app’s Discover tab, and the Verge reported that his following had more than tripled in the last year as a result of the promotion.

source: marketplace