![]()

Tech companies put a lot of work into designing their products to be “sticky.” That’s investor deck speak, but everyone knows what sticky really means: addictive.

While that may be good for the companies and their funders, a growing body of research is showing that it’s not so good for us users, and especially not for teens or kids. As the problem of tech abuse becomes better understood, tech companies may need to start measuring success by the quality of the time users spend with their products, not just the quantity. Discussions about the dangers of personal technology have been around a long time, but in the bubble of Silicon Valley it’s not a ready topic of conversation. People would rather talk about big ideas and their world-changing implications than about the unsavory by-products and unintended consequences that might come with them.

Speaking at a dinner Thursday night in Davos during the World Economic Forum, super-investor George Soros (whose fund owned several thousand shares of Facebook as of November) went on a tirade, comparing Google and Facebook to resource-extraction companies (“Mining and oil companies exploit the physical environment; social-media companies exploit the social environment.”) and to casinos (they “deliberately engineer addiction into the services they provide.”)

And: “Something very harmful and maybe irreversible is happening to human attention in our digital age,” Soros said. “Not just distraction or addiction; social media companies are inducing people to give up their autonomy.” Soros said now that it’s becoming harder to find brand-new users, social media companies have no choice but to please investors by demanding more of our time.

But he’s just the latest in a string of statements from important industry voices in the last few months.

On Wednesday Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff said Facebook should be regulated like a tobacco product. “I think that you do it exactly the same way that you regulated the cigarette industry,” Benioff said on CNBC’s Squawk Alley. “Here’s a product: Cigarettes. They’re addictive, they’re not good for you,” Benioff said. For someone of Benioff’s stature and reputation, this is a bombshell.

Earlier this month, a pair of Apple’s institutional investors raised the flag on adolescent smartphone abuse in January. The two investors, JANA Partners LLC and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, asked Apple to do something about the unhealthy amount of time kids spend with their iDevices (and the apps within). Apple should make sure its youngest customers grow up to be healthy adult Apple customers.

In response, iPhone co-creator Tony Fadell went on a tear on Twitter, saying that Apple, Google, Facebook, and Twitter design their products to addict not just kids but adults too. “Apple Watches, Google Phones, Facebook, Twitter – they’ve gotten so good at getting us to go for another click, another dopamine hit,” Fadell tweeted. “They now have a responsibility & need to start helping us track & manage our digital addictions across all usages – phone, laptop, TV etc.”

Apple itself responded publicly to the investors (and Fadell), saying it would add more parental control features to iOS. But it didn’t specify what kind, and gave no indication that it would respond to the concerns by adding features that weren’t already in the works. (There’s always lots of secrecy about additions to the OS, so we’ll have to wait and see.)

Another Apple institutional investor chimed in with the simple fact that everybody knows but don’t often say. “We invest in things that are addictive,” Investor Ross Gerber of Gerber Kawasaki Wealth and Investment Management told Reuters, commenting on the JANA/CalSTRS letter. “Addictive things are very profitable.”

An October interview in The Guardian quoted former Google, Twitter, and Facebook workers saying the products they worked on at the companies were designed to be addictive, and that “our minds can be hijacked.”

Napster founder and early Facebook investor Sean Parker said in November that Facebook was designed to take up as much of people’s time as possible. “God only knows what it’s doing to our children’s brains,” he said.

A REAL PROBLEM

God may not be the only one who knows what the effects of screens are. A growing body of research shows that many kids spend astonishing amounts of time staring at their phones. A Kaiser Family Foundation study found that kids between 8 and 18 spend 4½ hours a day watching TV or video on mobile devices. Add the gaming and social media on top of that and you have a good part of the day taken up by digital media. I’ve seen this up close in my nieces and nephews with their smartphones; it’s unnerving to see them so completely disengaged from the world (and the family) around them.

And the research is piling up, reinforcing again and again the contention that abuse of tech devices and apps robs kids of time they’d normally use for sleep, social time, studying, and exercise. It’s also been linked to a spectrum of mental health disorders, especially in (but not exclusively in) adolescents.

San Diego State psychology professor Jean Twenge has been among the most prolific researchers on the subject; she and her colleagues recently published research on how one million U.S. teens spent their free time and which activities correlated with happiness. One study found that those who spent more than three hours a day on a mobile device were 34% more likely to suffer “suicide-related outcome” than kids who used them two hours a day or less. Another finding showed that kids who used social media every day were 13% more likely to report feelings of depression.

Developmental behavioral pediatrician Jenny Radesky says kids are especially susceptible to harm from digital media because their brains are still developing and they respond to the content differently than other people. “Children are still developing their executive functions–their ability to self-regulate, plan out behavior, resist impulses, use their top-down cognitive controls to focus and complete tasks–so they are particularly susceptible to the novel enhancements (i.e., visual and sound effects, pop-ups), intermittent rewards, and persuasive design features of devices, apps, games, and online advertisements.” Radesky was one of the doctors who wrote the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for children’s digital media use.

Radesky says healthy apps that educate kids are available, like PBS Kids and Toca Boca; but kids often default to the free, featured, or most-downloaded apps on the app store. ” . . . a lot of these apps are low quality, very repetitive, or manipulative,” Radesky says. “My research lab has been playing some of them, finding some pretty inappropriate ways that apps try to get children to make in-app purchases.”

Tech companies and their investors may be forced to look at the word “addictive” as something other than an unconditional superlative. They might have to change the way they measure the success of their products from the number of hours users spend with them to the amount of “quality time” spent.

If the industry doesn’t make this shift, regulators might step in and make it for them. As more and more research comes out, the problem looks more widespread and more serious. Meanwhile, regulators around the world have become far more suspicious of tech companies–especially after the role tech companies played in the 2016 elections. These factors may create an environment where regulators are pressured to act.

FACEBOOK’S NEWS FEED CHANGE

Fear of regulation is one theory used to explain Facebook’s recently announced changes to its news feed. Chief executive Mark Zuckerberg announced in a Facebook post on January 11 that users will see less content from brands and publishers and more posts from friends, family, and groups. Zuckerberg also effectively admitted that there are ways of using Facebook that are actually bad for you. He said he believes that when users see content they can interact with (i.e., from people they know), not just consume passively, it’s better for their well-being.

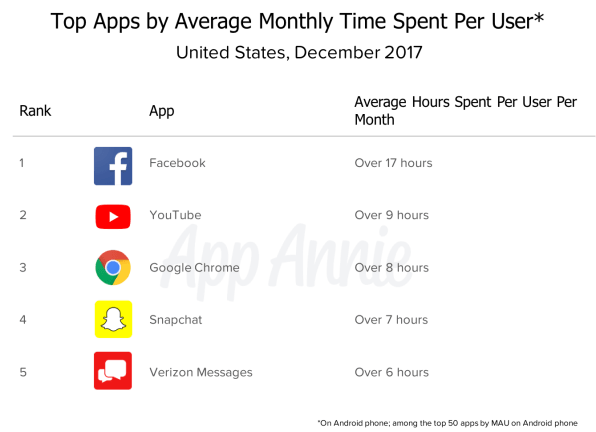

He’s talking about changing the way people use Facebook, but he’s also talking about a change to the time users spend there. “One of our big focus areas for 2018 is making sure the time we all spend on Facebook is time well spent . . . ,” Zuckerberg writes. And at the end: ” . . .by making these changes, I expect the time people spend on Facebook and some measures of engagement will go down. But I also expect the time you do spend on Facebook will be more valuable.” Less overall time. Less vegging out. More engagement. In other words, more quality time.

Stratechery‘s Ben Thompson believes the change wasn’t driven by a fear of regulation so much as it was by a sense of self-preservation. “The only thing that could undo Facebook’s power is users actively rejecting the app,” he writes in a January 17 post. “And, I suspect, the only way users would do that en masse would be if it became accepted fact that Facebook is actively bad for you—the online equivalent of smoking.”

Indeed, it is hard to imagine how governments could regulate the tech companies when it comes to the mental health effects they have in users–aside from requiring some kind of warning label. But the danger Thompson mentions for Facebook might still apply to Facebook and to other tech companies. What if consumers begin to see tech companies as heartless, profit-hungry, dopamine dealers? The user experience might begin to feel very different.

Of course, some tech companies are more at risk of this than others, depending on their business model. But the ones that measure success with a heavy focus on “engagement time” should broaden their worldviews to focus on “quality time” and responsible use. They’d be wise to come around to that way of thinking, just as their customers are starting to do.

source:-.fastcompany